Serialisation increases batch size and cycle time

When designing applications for Continuous Delivery, our goal is to grow an architecture that minimises batch size and facilitates a low cycle time. However, architectural decisions are often local optimisations that value efficiency over effectiveness and compromise our ability to rapidly release software, and a good example is the use of object serialisation and pseudo-serialisation between consumer/producer applications.

Object serialisation occurs when the producer implementation of an API is serialised across the wire and reused by the consumer application. This approach is promoted by binary web services such as Hessian.

Pseudo-serialisation occurs when the producer implementation of an abstraction encapsulating the API is reused by the consumer application. This approach often involves auto-generating code from a schema and is promoted by tools such as JAXB and WSDL Binding.

Both object serialisation and pseudo-serialisation impede quality by creating a consumer/producer binary dependency that significantly increases the probability of runtime communication failures. When a consumer is dependent upon a producer implementation of an API, even a minor syntax change in the producer can cause runtime incompatibilities with the unchanged consumer. As observed by Ian Cartwright, serialising objects over the wire means “we’ve coupled our components together as tightly as if we’d just done RPC“.

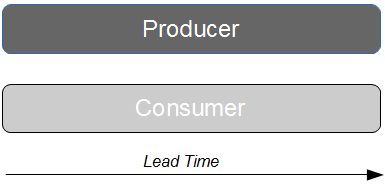

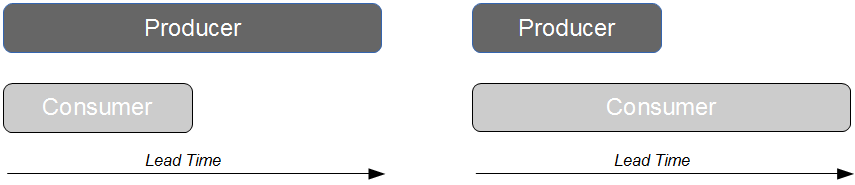

A common solution to combat this increased risk of failure is to couple consumer/producer versioning, so that both applications are always released at the same version and at the same point in time. This strategy is enormously detrimental to Continuous Delivery as it inflates batch size and cycle time, with larger change sets per release resulting in an increased transaction cost, an increased risk of release failure, and an increased potential for undesirable behaviours.

For example, when a feature is in development and our counterpart application is unchanged it must still be released simultaneously. This overproduction of application artifacts increases the amount of inventory waste in our value stream.

Alternatively, when a feature is in development and our counterpart application is also in development, the release of our feature will be blocked until the counterpart is ready. This delays customer feedback and increases our holding costs, which could have a considerable economic impact if our new feature is expected to drive revenue growth.

The solution to this antipattern is to understand that an API is a contract not an object, and document-centric messaging is consequently a far more effective method of continuously delivering distributed applications. By communicating context-neutral documents between consumer and producer, we eliminate shared code artifacts and allow our applications to be released independently.

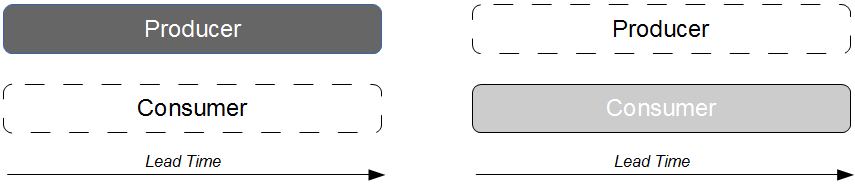

While document-centric messaging reduces the risk of runtime incompatibilities, a new producer version could still introduce an API change that would adversely affect one or more consumers. We can protect consumer applications by implementing the Tolerant Reader pattern and leniently parsing a minimal amount of information from the API, but the producer remains unaware of consumer usage patterns and as a result any incompatibility will remain undetected until integration testing at the earliest.

A more holistic approach is the use of Consumer Driven Contracts, where each consumer supplies the producer with a testable specification defining its expectations of a conversation. Each contract self-documents consumer/producer interactions and can be plugged into the producer commit build to assert it remains unaffected by different producer versions. When a change in the producer codebase introduces an API incompatibility, it can be identified and assessed for consumer impact before the new producer version is even created.

By using document-centric messaging and Consumer Driven Contracts, we can continuously deliver distributed applications with a low batch size and a correspondingly low cycle time. The impact of architectural decisions upon Continuous Delivery should not be under-estimated.