Pipelining inter-dependent applications as uber-artifacts is unscalable

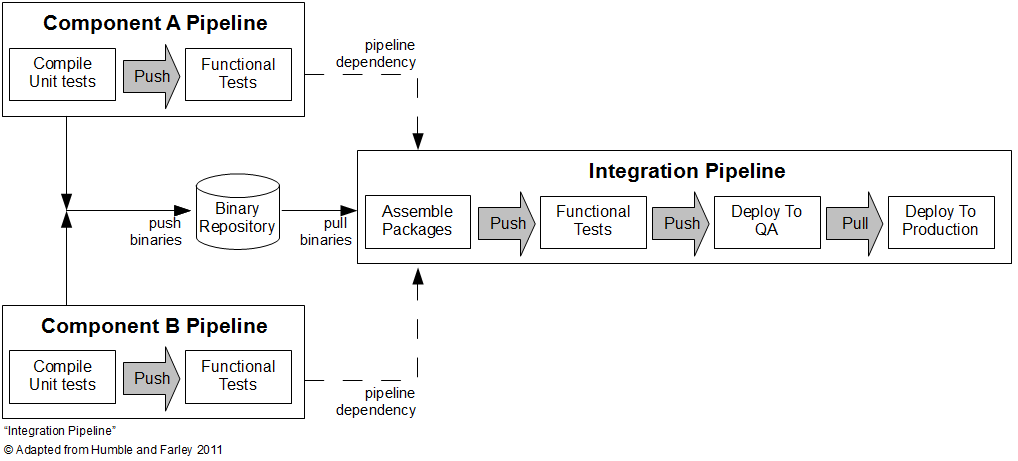

Achieving the Continuous Delivery of an application is a notable feat in any organisation, but how do we build on such success and pipeline more complex, inter-dependent applications? In Continuous Delivery, Dave Farley and Jez Humble suggest an Integration Pipeline architecture as follows:

In an Integration Pipeline, the successful commit of a set of related application artifacts triggers their packaging as a single releasable artifact. That artifact then undergoes the normal test-release cycle, with an increased focus upon fast feedback and visibility of binary status.

Although Eric Minick’s assertion that this approach is “broken for complex architectures” seems overly harsh, it is true that its success is predicated upon the quality of the tooling, specifically the packaging implementation.

For example, a common approach is the Uber-Artifact (also known as Build Of Builds or Mega Build), where an archive is created containing the application artifacts and a version manifest. This suffers from a number of problems:

- Inconsistent release mechanism. The binary deploy process (copy) differs from the uber-binary deploy process (copy and unzip)

- Duplicated artifact persistence. Committing an uber-artifact to theartifact repository re-commits the constituent artifacts within the archive

- Lack of version visibility. The version manifest must be extracted from the uber-artifact to determine constituent versions

- Non-incremental release mechanism. An uber-artifact cannot easily diff constituent versions and must be fully extracted to the target environment

Of the above, the most serious problem is the barrier to incremental releases, as it directly impairs pipeline scalability. As the application estate grows over time in size and/or complexity, an inability to identify and skip the re-release of unchanged application artifacts can only increase cycle time.

Returning to the intent of the Integration Pipeline architecture, we simply require a package that expresses the relationship between the related application artifacts. In an uber-artifact, the value resides in the version manifest – so why not make that the artifact?