(available on LinkedIn)

When I advise senior technology leaders, I like to understand how they work, so I can adapt my style to help them succeed. So when they’re thinking about making changes, I’ll ask:

How do you want to manage feedback for this initiative, from concept to execution?

That tells me whether they see feedback as:

- Data points to set a direction, or validate a decision

- Conversations to be designed, or cascaded sequentially

- Opportunities to learn, or boxes to tick

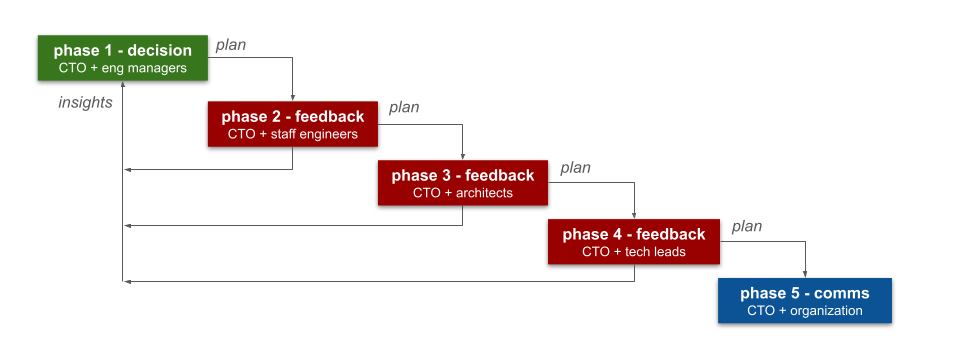

There’s lots of feedback models. I call one of them the feedback waterfall, and I advise against it. It’s when a well-intentioned person asks for feedback to validate a decision, and seeks learning opportunities by cascading conversations sequentially through their organisation.

For example, a fictional CTO is frustrated with her organisation’s Scala tech stack, due to skills scarcity and salary costs. She decides on a transition to Kotlin. She runs a workshop with her engineering managers, to gather feedback and draft an execution plan. She then shares the plan, one group at a time, with her staff engineers, architects, and tech leads, to collect more feedback. Finally, she announces the plan to the organisation, and expects teams to begin the transition. This feedback model looks like a waterfall, because it’s a waterfall.

I understand the appeal of a feedback waterfall. By shaping the Kotlin decision with her engineering managers, the CTO is shielding a fragile, early stage idea from the tyranny of the herd – the noise of unstructured discussions, dominant voices, and scattered opinions. And in theory, the execution plan is strengthened by the downward flow of feedback, with each group gradually brought into alignment.

But a feedback waterfall results in:

- Scepticism. Staff engineers, architects, and tech leads aren’t sure if the CTO genuinely wants their ideas, because the Kotlin transition is pencilled in and it anchors conversations. Commitment is weakened, because people dislike blurring feedback with communication.

- Resentment. Engineering managers don’t contribute after phase 1, so they feel sidelined. Staff engineers, architects, and tech leads don’t contribute until phases 2, 3, and 4, so they feel disempowered. Testers aren’t invited at all, so they feel excluded. Energy shifts away from collaboration, because people resent the process.

- Delays. It takes weeks for the CTO to complete phases 2, 3, and 4. An engineering manager is on holiday. Staff engineers are at an offsite. An architect is sick. Tech leads are busy with business deadlines. Critical insights arrive slowly, because people aren’t immediately available.

- Friction. The CTO has to revisit her decision in phases 2, 3, and 4. Staff engineers say they mentor junior engineers in advanced Scala. Architects warn the messaging system depends on Scala types. Tech leads reveal there are internal libraries lacking Kotlin bindings. Valuable insights risk rejection, because people lack time and energy to revisit past conversations

Senior leaders don’t usually feel the pain, because they’re the first person in phase 1, and the only person in every phase. And they can make mistakes, just like me or anyone else. They might accidentally exclude someone, or mix teams in different phases. They might believe alignment requires agreement from everyone, and seek consensus in every phase. They might start treating feedback as a tick-box exercise if a phase is too slow. Those situations only add to the scepticism, resentment, delays, and friction.

I’ve seen and contributed to too many feedback waterfalls, and they’ve always led to under-informed decisions and suboptimal execution. And it’s hard to persuade senior leaders to change how they manage feedback, because they’re people, and there’s always reasons behind reasons. Feedback waterfalls aren’t really about senior leaders protecting their ideas from the tyranny of the herd – they’re protecting themselves. They fear messy workshops, design by committee, or a loss of control. They lack the appetite or skills to navigate the ambiguity, creative tension, and unresolved views of open conversations.

There are better ways of managing feedback for an initiative, from concept to execution. The Scala CTO might have asked for feedback on her frustrations before making a decision, been clearer about what was open for discussion, and run parallel feedback phases afterwards. But before that, we need to talk more openly about why feedback waterfalls are so appealing, and so damaging.

Leave a Reply