Consumer Release Testing is high cost, low value risk management theatre

Despite the historical advice of Harold Dodge that “you cannot inspect quality into a product” and the contemporary advice of Don Reinertsen that “testing is probably the single most common critical-path queue” the Release Testing antipattern remains prevalent in the IT industry, and is by no means limited to standalone applications.

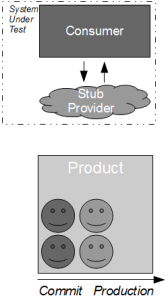

Consider the development of a consumer application that requires data from a provider application in order to fulfill its business capabilities. The consumer team contains developers and testers collaborating upon the Testing Pyramid strategy, which recommends unit/acceptance tests over end-to-end tests on the basis that test execution time is proportional to System Under Test scope. This means the necessary provider interactions are test-driven by the consumer team using the Test Stub pattern, which creates a lightweight provider implementation to supply canned responses back to the consumer.

By using a stub the consumer interactions with the provider can be tested in a minimal System Under Test, which ensures that changes made by the consumer team produce fast and deterministic feedback. Success and failure scenarios (e.g. socket failure, socket timeout, provider error code) can be rapidly developed without relying upon a running provider instance, and the consumer team should be capable of rapidly responding to changing requirements in the future.

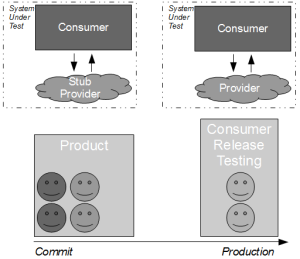

However, in many IT organisations the consumer team will be hindered by Consumer Release Testing – a phase of post-development end-to-end regression testing of the full consumer and provider stack, performed by a segregated testing team on the critical path.

The desire for provider risk mitigation is understandable given that consumer revenues are to an extent dependent upon the provider, but Consumer Release Testing exacerbates the original flaws of Release Testing:

- Extensive end-to-end testing – including both consumer and provider in System Under Test scope increases test execution time and maintenance costs

- Independent testing phase – dividing authority and responsibility for the consumer results in quality issues and feedback delays

- Critical path constraints – working on the critical path means the release testers will always be pressured to reduce test coverage to meet pre-agreed deadlines

By extending the Release Testing strategy it is evident that Consumer Release Testing is itself risk management theatre – it is highly unlikely to uncover any substantial defects in consumer/provider interactions without a significant increase in test coverage, which will drive up product lead times and opportunity costs.

A far more effective risk reduction strategy is to accept the conventional wisdom that testing is an activity not a phase, and move the blameless release testers into the consumer product team. This ensures that all team members are equally invested in product quality and empowers testers to focus upon higher-value activities such as exploratory testing, which has been described by Elisabeth Hendrickson as “particularly good at revealing vulnerabilities that no one thought to look for before“. For example, some exploratory testing off the critical path of the consumer against a running provider instance might uncover some additional error scenarios that would then be fed into the automated unit/acceptance tests.

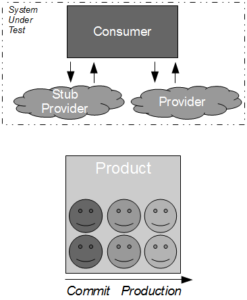

A high value, low cost alternative to Consumer Release Testing is for the consumer and provider to actively cooperate in risk reduction, which can result in a substantial reduction in provider risk. The probability of a provider failure can be decreased by independently testing the conflated concerns of end-to-end testing as follows:

- Connectivity: the consumer can test provider expectations of consumer connections via release time smoke tests and run time monitoring

- Compatibility: the provider can test consumer expectations of messaging via build time Consumer Driven Contracts issued by the consumer

- Conduct: the consumer can test its expectations of provider behaviour via build time API Examples issued by the provider

The cost of a provider failure can be reduced via incremental release strategies such as consumer-side Feature Toggles and provider-side Blue-Green Deployments. These practices encourage a provider release to be gradually phased into production usage, so that the consumer can switch back to the previous provider version if necessary.

This approach is a viable alternative to Consumer Release Testing, but it is of limited value without provider cooperation. If the provider cannot or will not participate in risk reduction then the consumer must assess risk based upon historical provider lead times. As large batch sizes increase risk an infrequent provider release schedule is indicative of heightened risk, and if the cost of failure is significant then a limited form of Consumer Release Testing may be deemed justifiable. In those circumstances the consumer development team should perform end-to-end tests off the critical path using a lightweight test client, so that the slow feedback loops and non-determinism of Consumer Release Testing are diminished.

Hi Steve,

Interesting post and I agree that testing should be considered an activity which takes place alongside development. You talk about it towards the end of the post but I think that one of the most damaging aspects of having an isolated test team (assuming they are the only test team) is to encourage developers to ‘throw things over the wall’ for testing. Fully integrated teams are far more likely to collaborate and take a team-wide view of quality. The exception to this is where you have smaller teams of cross-functional people building and testing but maintain an independent test team to exploratory test across the whole system. I believe that it is possible to do this well, and it may uncover some very interesting defects. It is incorrect to consider that significant defects can’t be uncovered without high test coverage. I can think of many systems which crash the first time I try to use them. In fact you’re touching on one of testing’s great challenges; you simply cannot predict where the defects lie or which tests will expose them.

I’m interested in your point that ‘Independent testing phase – dividing authority and responsibility for the consumer results in quality issues’ do you see this simply because the developer doesn’t need to accept so much responsibility for their work?

Amy